James & Catherine McKinnon

Part 1

Source: Helen Schmidt in From Sage to Timber history book

James was the son of James and Mary McKinnon and was born August 21, 1865, at Welwood, Manitoba.

Catherine was the daughter of Alexander and Catherine McRae and was born October 2, 1875, at Teaswater, Ontario.

Catherine and James were married in 1897. They had four children: Lena (Oscar Schmidt), Clifford (Nellie Visser), Mary (Keith Dodds) and Dora (John Pelkey).

They came to the Cypress Hills in the summer of 1900 from Manitoba. They settled within two miles of the site of old Fort Walsh, in a little coulee known as “Flapjack Coulee” on the SW 17-7-29 W3rd. There they started ranching in a small way with some cattle that they had brought with them from Manitoba. Isaac Stirling, who was later to become a member of the newly formed Saskatchewan Legislature, was in partnership with them.

In 1905 they moved down on Battle Creek to a choice location between the present towns of Consul and Vidora

James McKinnon’s sister, Mary, also came to the Cypress Hills area and was married to a gentleman whose name was also MacKinnon (note different spelling). They had six children: Barbara (Shillings), Grace (Lemm), Mary (Harper), Margaret (Daunahue), Jack (Maggie Noble) and Doug (Violetta Pettyjohn).

Interesting Note:

Mary McKinnon and her husband, spelled MacKinnon, had a son, Jack, who married Maggie Noble; they lived at Fort Walsh from 1926 to 1933.

Part 2

Source: Our Side of the Hills History Book

(Reprinted with permission from “Canadian Cattlemen – The Beef Magazine” – cattlemen.ca. From the December 1946 issue.)

The following article was written by T.L.Shepherd and appeared in the “Canadian Cattleman” December, 1946.

The life of Mrs. Jim McKinnon is a page of the fast-changing history of Western Canada. Printed in “Canadian Cattlemen” it will remain a permanent record, entertaining reading for older members and, I hope, inspiring reading to younger folks. For this fine lady, now retired and living in the little town of Consul, Saskatchewan, has seen the Old West change from open unfenced range, to dry farming, dried out farming and now PFRA irrigation in large blocks.

Born Catherine McRae on a small farm four miles from Teeswater, Ontario, she came to Manitoba at the early age of two years. Her parents loaded their team and wagon and some household effects on a fairly large boat and came up Lake Superior to the landing at Glendon, near the Lake-of-the-Woods from whence her father started overland to Portage La Prairie. To make this journey he had to dip down into the U.S. and the northeast corner of North Dakota. There he made his first contact with the “tumbling tumble weed”. This weed didn’t please his eastern horses at all and he had to watch very carefully to see that they didn’t run away with his wagon and all their worldly goods.

Mrs. McRae came by a much smaller boat with Catherine and her younger brother, Bill, up the Assiniboine River to Portage La Prairie where she rejoined her husband. They bough land and farmed it successfully for about five years. Later, they lived for some time in the Riding Mountain District and then moved to Dauphin, Manitoba. At the age of twenty two she married James McKinnon and a little more than a year later, their first child, Lena, was born.

Like so many young people of that day and age, they too, heeded the call of the west and in the summer of 1900 came to the little cowtown of Maple Creek. Heading southwest up into the Cypress Hills they settled within two miles of the site of the old Fort Walsh, on a little coulee known as Flapjack Coulee. There they started ranching in a small way with some cattle they had brought with them from Manitoba. Isaac Stirling, later to become a member of the newly formed Saskatchewan Legislature, was in partnership with them. In fact, they had worked together wintering cattle in Manitoba before they came west.

On November 7 that fall, the second member of the young family arrived. This was Clifford, their only son. Although there was a doctor in Maple Creek Mrs. McKinnon decided to stay in her own log cabin where a neighbor lady, Mrs. Ball, came to help her. Life wasn’t easy in those days, but still most of the folks seemed to get along some way.

Although the Cypress Hills was and still is a very good ranching area it was becoming crowded even by this early date. To the south lay the short grass plains, extending clear to the Milk River in Montana. Although there was very little shelter and none too much water down on the flats, the short grass made very good grazing for both cattle and horses, if they could withstand the winters.

In the summer of 1905 the McKinnons, now with a third child, Mary, moved down on Battle Creek to a choice location between the present towns of Vidora and Consul. Here there was plenty of free range, good hay flats and running water. What if it was fifty five miles to the nearest town of Maple Creek and thirty miles to the closest timber. You couldn’t expect everything now, could you?

Mrs. McKinnon says that she remembers very clearly the first morning in their new location. As she parted the tent door to look out, the first thing she saw was a fine buck antelope. This seemed almost like a good omen to them, for strange as it may seem, antelope were not as numerous in those early days as they are right now. The antelope, being a very curious animal, was no doubt attracted by the white flapping tent.

The land settlement had spread down from the Fort Walsh area with only a few sections each side of the creeks being surveyed at that time. Even this land survey stopped at the south edge of township five, two miles north of where McKinnons wanted to locate. As they did not want to put their buildings on what later may be a road allowance they decided to measure two miles from the township line. They hadn’t a surveyor’s chain or steel tape so they hit on a plan of putting a set of hobbles on a man’s leg and joining them with a piece of light chain. By adjusting the length of this chain they could make each step just a yard long.

That gave them the distance, but how about the direction? Of course, there were no fences or roads to guide them, but the good Lord provides many things, including the North Star. So they set up stakes one clear night and the next day ran their survey line. They were very pleased to find several years later that they had only missed their mark by a matter of a few feet.

They were not long in getting logs from the Hills to build a small log cabin. Later they built a barn and corrals for their livestock. They had no trouble finding plenty of native hay to stack so soon they were well settled for the coming winter.

No story of the early days of the west would be complete without some mention of the hard winter of 1906 and 1907. With a small herd of cattle the McKinnons came through with the loss of only one animal, for about Christmas time their cows, with some sixth sense, decided that they would be better off in the shelter of the Forest Reserve than out on the open plains. So in a bunch they moved back to the Hills. This proved to be a wise move for the folks had none too much feed for the calves and a few horses that they kept in the barn.

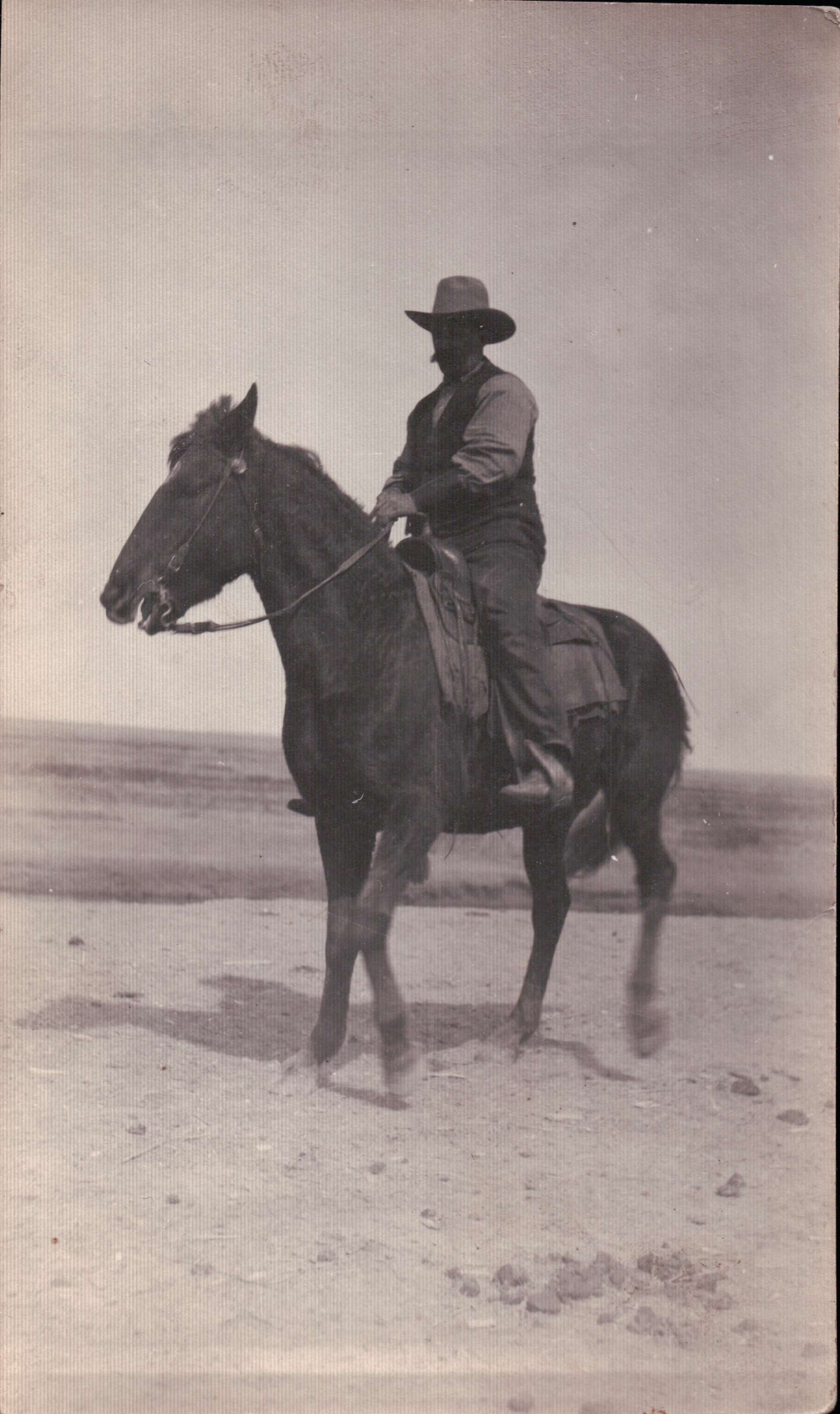

On the third of February, 1907, Mrs. McKinnon decided that she would go to Ten Mile Post Office for the mail and two bags of wheat for chicken feed. She left her husband and his sister to look after the children, now numbering four, while she hitched a single horse to a toboggan and started on her twenty five mile journey. The snow lay deep and crusted so the trip took her all day. Her folks had moved from Manitoba to a few miles west of the Ten Mile Detachment so she went on over to visit them. Starting home a day or two later she was very pleased to learn that Rube Gilchrist, then a strong young man, was just a few miles ahead of her. He was headed to his home about three miles up the creek from McKinnons. She felt that Rube knew the country like a book and he would choose the places with the least snow. All that day she followed this lone rider, but could not manage to catch up to him, but as long as she could see the figure from each hilltop and follow his horse’s tracks across each hollow she felt fairly safe. When she came to the Gilchrist home that evening she was plenty glad to call it a day and not try to continue the few miles on to her own home that night.

Her husband had been coming from the bush with a load of wood in the late fall of 1906. As his team became very tired about ten miles from home and as there was no place to stay overnight he decided to unload and continue with the empty wagon. Thinking that it might snow before he returned he stacked his load of dry wood in the form of a teepee. As it happened he didn’t haul that load of wood until the following spring and found that three head of cattle had taken shelter in his teepee and died there. What do sailors say, “Any port in a storm”. Too many storms for those cattle that winter!

By April 7 that spring the McKinnons were running very low on hay for their calves and food for themselves so they decided to go to Maple Creek. The shorter Whitemud Road, now Highway 21 past the Cypress Hills Park, was still blocked with snow, but they learned that the road was open to Maple Creek via Fort Walsh. So they took a sleigh that far and borrowed a wagon for the rest of the trip. Even at that late date the snow was still up to the horses’ breeching in places. But they made the trip, returning with supplies for the family and oats for the livestock. They came through that winter without the loss of a calf.

What happened to the older stock that had headed back to the Hills that winter? That spring they found them all except one steer. They had wintered fairly well without a forkful of hay, proving once more that the Cypress Hills was a good ranching area.But what had happened to the steer? That they could never find out, but could only guess that someone needed fresh beef for in those days of open range some animals reached several years of age before they were branded. Once a calf had left its mother it was almost impossible to tell who it belonged to, so it then became the property of the first man with a hot branding iron, a long rope and a good horse. These slicks, as they were called, were looked on in much the same light as big game in an open season today. If a family needed meat, why not shoot one of the strays? In the wintertime it was not always easy to see a brand, especially when the animal’s coat was long and shaggy. More especially, if a person was short of meat and the animal in question was in first class condition to butcher.

After that winter the McKinnons decided that perhaps they should try to grow a little grain to help out on the feed for their livestock. That year of 1909 was very favorable and they had a lovely patch of oats growing in a bend of the creek. The homesteaders were starting to come into the south country here and many were misled by this very nice crop of oats. But the summer of 1910 was very different. The oats came up real nice until they were about 18 inches high, then the hot chinook winds struck and they burned white within a space of a few days. That fall they were short of feed so sold some cows at $23.30 a head with the calves thrown into the deal. Heart breaking, wasn’t it?

Here was nice level land, and a creek running by, so why not start an irrigation project? After digging miles of ditches with four mules and a fresno they found, like so many other would-be irrigators on Battle Creek, that the stream ran dry when water was needed most. Jim McKinnon could see how the flood water of Battle Creek could be diverted into Cypress Lake and later turned back into the creek when it was needed. He talked about the plan for years, but no one could see it until four years after he died, when the PFRA started to work in the fall of 1937.

With a family of four children to raise and with times none too good, it wasn’t all sunshine by any means. But rain or shine the McKinnons maintained a happy, carefree household. There was often a hired man or two and always callers stopping for meals or overnight. As well as this, Mrs. McKinnon boarded a mounted policeman, Reg Warren, and his horse for three years. Then the engineers surveying the railway through their land also made their headquarters at her home. With part of the extra money earned this way, Mrs. Jim felt that they could afford to hire a private teacher for their four children. Vada Curtis, now Mrs. Russell Kennedy of Consul, taught the McKinnon children and as part of the agreement brought her own younger brother along to school, too.

They were fortunate in the choice of this lovely and talented girl of fifteen. For as well as teaching the children in the day time, they had a piano that she used to play while all the family and visitors would gather around in the evening to sing the old songs. Very often there would be a dance and for a change, the boys would try their hand at all kinds of gymnastics or have a few rounds of boxing. It was no small job to provide food day after day for a household of this size. Mrs. McKinnon was telling me that she used to bake three batches of bread every two weeks. But what bakings they were – fifteen to sixteen loaves every time!

An old man only known by the name of Yorky called for dinner one winter day. About a week before, he had sent a small check into Maple Creek with a near neighbor, Mr. McMurchy, with the request to bring some tobacco and a large can of baking powder. The old fellow lived in what was known as a dugout, just a rough cellar with some poles and dirt for a roof. That was up towards Cypress Lake, about six miles north of McKinnon’s. When McMurchy hadn’t returned with his supplies and change he thought that he’d walk up the trail to meet him. Getting his supplies and with his change he struck west for his dugout when a severe winter storm came up. Later it was learned that he didn’t reach his so-called home, in other words, he was listed missing.

Nobody worried a great deal for these homesteaders had a habit of getting disgusted and just leaving the district. However, one day Jim McKinnon suggested to a young fellow who was staying with them and known as Dakota Jack, that they should go out and find “Poor Old Yorky.”Jim was a keen coyote hunter, so taking the hounds in a home-made toboggan, he hitched up his team while Dakota Jack rode saddle horse. Up towards the lake they startled a coyote and at once gave chase. Dakota Jack dashed ahead, but his saddle horse put his foot in a badger hole and down they went in a cloud of flying snow. Jim dashed by with his team giving just one glance to see that Jack wasn’t hurt. The coyote ran in a semi-circle and the hounds soon pinned him down.

By the time Jack got back on his horse the hunt was all over so he cut across to rejoin his companion. What should he happen across, yes, you’ve guessed, it was Yorky. The next day they drove up to the Ten Mile Detachment to notify the police, but they took the team and sleigh and brought home a load of wood with them. This was before the Mountie was stationed at their place. The police came down the following day and Jim guided them back to the old fellow. Digging away soft snow they found him with his change and tobacco in his pockets, his head resting comfortably on the big can of baking powder, sleeping well, but permanently. The police took him to McKinnon’s that day, on to the Ten Mile the next day and from there on to the Maple Creek Cemetery.

The McKinnons were always willing to try something that might better their position. Jim got the idea that as there was a good sale for mules, why not raise some from the very plentiful range mares? So he went to Red Deer Smith’s north of Maple Creek and paid $1100 for a Jackass. This was considered a small fortune back in 1911. He managed to raise a lot of mules, but I am getting ahead of my story. This Jack got loose one night and chewed quite a hole in the top of a shoulder of a little saddle mare. In time she got better, but was still pretty touchy about it.

Unusually heavy rains in the fall of 1911 brought a flood down Battle Creek. Jim rode across to get the cows on this little mare with the sore neck. As the water rose higher he lifted his feet out of the stirrups and leaning forward in the saddle, happened to touch the mare on her sore neck. She ducked her head down fast right into the deep water. Then she tossed it up again, catching Jim off balance and hitting him a hard blow on the forehead. The big buckle on the top of the riding bridle cut him over one eye while the force of the blow knocked him out. He promptly fell off the horse into four feet of cold water which brought him to again. Who said they didn’t see action in those days!

He waded out of the creek and, still bringing the milk cows home with him, arrived in a pretty dazed and chilled condition. Mrs. Jim took good care of him, but within a few days they noticed that his neck was getting a bad color and the flesh starting to decay in spots. They called on another neighbor, Doctor Offerman, a chiropractor doctor, who examined him and said there was nothing wrong except that he had a broken neck! Calling on the aid of this strong young man, Dakota Jack, they pulled and yanked his head around until they got the bones back in place. All this in a log house fifty miles from town.

The McKinnons were both keen coyote hunters and always kept a pack of hounds. Each fall, they would go off for a hunt and visit, going first about ten miles north to the Wylie Ranch then across country to Walter Boyd’s on the Six Mile and later over to Jackie MacKinnon’s at Fort Walsh. They were both keen on good horses, too, and at one time kept both a Blood and Standard-Bred stallion. Hitching this pair to a democrat they had a really spirited team of drivers. Startling a coyote, they’d give the team their head and away they’d go, hell for leather. I guess that it was a great sport and the sale of coyote hides brought in a little welcome cash to the family funds, too.

For a number of years they had quite a band of sheep. In the fall of 1918 they loaded a wagon with bales of wool and crossed over to Chinook, Montana where they sold it for forty eight cents a pound. Then they headed their big team of mules twenty five miles west to Havre where they laid in a stock of supplies. It was a good forty miles from Havre to the first house on the Canadian side of the line, the Worthy home. It was a cold, raw fall day and they still had several miles to go when, who should catch up to them but Roy Worthy. Now he drove a Model T Ford coupe, a car I can still remember very well. Pulling up beside McKinnons he stopped and suggested that as they were going to stay at his place that night, wouldn’t Mrs. Jim ride the rest of the way in the comfort of his closed car? With that winning smile of hers, she thanked him kindly and added, “I’ve come a long way with Jim already (meaning a long married life) and I guess a few more miles won’t do any harm”. That’s loyalty for you!

Jim died in the spring of 1933, but Mrs. McKinnon carried on the place alone until a few years ago. She then sold most of her irrigable land to the PFRA and is now retired and living in the little town of Consul. She spends a lot of her time in the cafe; the door seldom opens without admitting one of her friends. Be it a commercial traveller or an old time rancher, she knows them all and they all stop to exchange a few pleasant words with Mrs. Jim.

With a slow manner of speaking and a very friendly nature she has a heart-warming smile that wins everyone to her. She has always taken in all the dances and concerts for miles around. She doesn’t dance much now, but not many years ago she won first prize in the old-time waltz contest. Her partner was Dewey Barwis of Govenlock, whose father was a Mountie at old Fort Walsh.

There are many tales still told of the hospitality of Mrs. Jim and her husband in the early days. Fellow rancher or new homesteader, they were always sure of a warm welcome at the McKinnon home; they never let the troubles of the world rest very heavily on their shoulders and were always out to see the brighter side of life. Now, at 71, Mrs. Jim McKinnon has a smile for everyone and is always ready with a good story of the early days. Truly a fine example of pioneer womanhood, the type that did their share and more in the development of Western Canada. Mother of four, grandmother of ten, she is the friend of the whole countryside.

Added note: Mrs. Catherine (Kate) McKinnon died on April 17, 1951 and was buried in the Consul Cemetery beside her husband.