Early Ranchers

Courtesy of the Gaff Collection

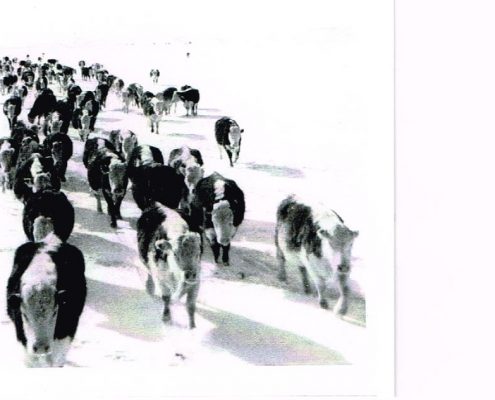

Ranching developed where physical and climatic features combined to provide sufficient natural grassland for livestock – primarily beef cattle but also sheep – to graze relatively independently year-round. It began in the BC interior in the late 1850s, and was encouraged by markets created by the gold rushes. Livestock was brought in from the western US and expanded quickly into British Columbia valleys, the Rocky Mountain foothills and eventually into the Cypress Hills and semiarid plains of southeastern Alberta and southwestern Saskatchewan.

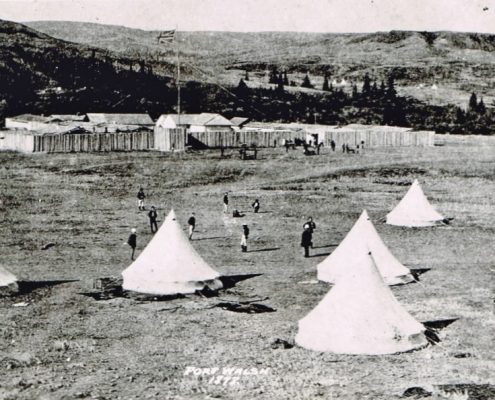

Numerous policemen joined the ranching fraternity when their terms of enlistment expired, thus forming a distinctive core about which the industry developed and helping to define its emerging social character. The British-Canadian orientation of the ranching frontier was reinforced by the arrival of Englishmen attracted by the great publicity accorded in Britain to North American cattle ranching. They typically described themselves as “gentlemen” and came generally from the landed classes, with sufficient capital to establish their own ranches.

Access to distant markets was assured when the Canadian Pacific Railway reached the prairies in the early 1880s, and interest in ranching grew dramatically. The railway, however, also brought the threat of general settlement, especially in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and an accompanying grid of barbed wire fences. Ranchers were determined to keep the “sodbusters” out and settlers were equally bent on penetrating the grazing leases. Finally the government yielded to the overwhelming demand for open settlement: in 1892 the ranchers received four years’ notice that all old leases restricting homestead entry would be cancelled.

But the powerful cattle compact argued that the ranching regions were too dry for cereal agriculture. Recognizing that the upper hand was with those who controlled the water supply, cattlemen persuaded Ottawa to protect the cattle industry by setting aside major springs, rivers and creek fronts as public stock-watering reserves. Most choice sites thus became inaccessible to settlement, and the ranchers’ dominance continued.

After the election of Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals (1896), the cattlemen faced a government committed to unrestricted settlement. Convinced that dryland agricultural techniques were surmounting the obstacle of moisture deficiency, the Liberals began to auction off the elaborate system of stock-watering reservations. The spirited defence of the ranchers’ cause by stock growers’ associations, and strong beef markets, only slowed the decline of the industry. Soon in full retreat before the rush of homesteaders who settled on even the most marginal lands in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, the faltering cattle kingdom was dealt the ultimate blow by nature. Whereas homesteaders had enjoyed years of above-average rainfall, the harsh winter of 1906-07 was without the accustomed chinook, bringing stock losses in the thousands for many large-scale ranchers.

The passing of the great cattle companies in Alberta and Saskatchewan brought a new generation of local ranchers to prominence. At the same time the predominantly American origin of most dryland settlers, and heavy WWI enlistments and casualties sustained by the British-Canadian population, combined to change profoundly the social character of the ranch country.

Nonetheless, during the war ranchers’ fortunes began to improve: their political party had returned to power in Ottawa, beef prices were buoyant and the return of a dry cycle caused settlement in the region to ebb. A decade later the ebb became a flood and the out-migration of thousands of drought-driven refugees in the 1930s brought grudging recognition that the cattlemen had pioneered, and would carry on, an enterprise especially suited to semiarid environments.

(Source: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ranching-history/)

Highlighted here are the people who were the pioneers of ranching in this area.